Lodz Ghetto - Deportations and Liquidation

Deportations

On December 7, 1941, the first Nazi death camp located in Chelmno, some seventy kilometers from Lodz, began its experimental run. The killing vans in which the victims were suffocated by means of exhaust fumes replaced the execution squads of the Einsatzgruppen as both more efficient and less “disturbing”. These vans remained in use until July 1944. Over 250,000 Jews from Wartheland were annihilated in Chelmno. Of this number, over 70,000 came from the Lodz ghetto.

The first hint of impeding deportation came in a speech by Rumkowski on December 20, 1941, when he announced that a contingent of 10,000 persons had been requested by the Germans for deportation. He further stated that this contingent would be filled with criminal elements and welfare recipients who did not participate in the public works program.

On December 30, 1941, an announcement was issued that until further notice all ghetto residents were strictly forbidden to shelter strangers or relatives not registered as members of the household. Finally, on January 5, 1942, the Resettlement Commission nominated by Rumkowski began compiling lists of deportees.

Deportations to and from the Lodz ghetto in 1942 were in step with the Nazi policy of disposing of all unproductive groups including children and old people. The Lodz ghetto was to become a labor camp where nothing mattered but work. Those few survivors of the destroyed communities who were deported to the Lodz ghetto in 1942 had been spared because they were skilled workers.

The first transport left Lodz for Chelmno on January 16, 1942.

The process resumed with an even greater intensity on February 22, 1942 and lasted until April 2, 1942. During this phase of deportations, 34,073 lives were extinguished. The total number of deportees between January and May 1942 was 54,990 persons, more than one-third of the ghetto population.

The next wave of deportation from Lodz was directed against the children, the aged and the infirm. This time the ghetto Jews had information of what was to happen and an attempt was made to hide some of the children among the ghetto work force in the summer months of 1942. By July 20, 1942, there were about 13,000 children and adolescents employed in the workshops and factories. However, younger children and old people could not justify their remaining in the ghetto.

In late summer 1942, it was decided that the liquidation of the Lodz Ghetto would be postponed and that it would continue to operate as a gigantic labor camp and important industrial center for the war effort. For this reason, two major operations were carried out in the ghetto, on the first to second, and the fifth to twelfth of September, to remove as many as possible, who according to Nazi criteria, were deemed to be unfit to be employed in the workshops and factories.

The deportation began on September 1, 1942 with the removal of the sick from five ghetto hospitals and two preventoriums. On this day, 374 adult and 320 children were deported to the death camp.

On September 5, 1942, a general curfew (Gehsperre in German, shphere in Yiddish) was announced until further notice. The residents of old age homes and orphanages were the first to be taken to the train.

After that, the Ordnungsienst (Jewish police) made house searches to find children and take them away from their parents. The results of the first day’s searches were so meager that the German ghetto administration and the Gestapo decided to take matters into their own hands, and the ghetto became the scene of a vicious manhunt. By September 12, 1942, it was all over. There were 600 dead in ghetto streets and homes. 15,859 victims had been taken to transports. On September 12, 1942, the curfew was lifted.

On October 1, 1942, the ghetto population numbered 89,446 inhabitants. The number of German sentries guarding the ghetto was reduced. The Lodz ghetto continued to exist as a huge labor camp. Representatives of the German Ghetto Board started visiting the labor departments to supervise production.

During 1942 and 1943 the usefulness of the Lodz ghetto to the Nazi war machine was beyond doubt, so much so that all attempts by Himmler and the SS to liquidate the ghetto were successfully frustrated by the manpower-starved Nazi armament authorities. Himmler’s plan to convert the ghetto into a concentration camp (which would bring it under the control of the SS) and transfer its much diminished population to the Lublin district, where they would become part of the slave labor complex under Odilo Globocnik, was never materialized.

The most important instrument of Rumkowski’s power, the distribution of food, was personally taken over by Hans Biebow, the chief of the German ghetto administration, in October 1943.

Liquidation

On June 10, 1944, Heinrich Himmler ordered the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto. The Nazis told Rumkowski who then told the residents that workers were needed in Germany to repair damage caused by Allied air raids. The first transport left on June 23, 1944 for Chelmno with many others following. On July 15, 1944 the transports halted. The decision had been made to liquidate Chelmno because Soviet troops were getting close. Unfortunately, the remaining transports would be sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On August 8, 1944, after a week of almost futile efforts of persuading the ghetto Jews to come to the trains, several German police units entered the ghetto and began to drag people to the railroad station. On August 9, 1944, all plants in the ghetto were ordered closed. That same day the western part of the ghetto was closed off and all residents were ordered to move to the eastern part.

The first transports to Auschwitz-Birkenau began to depart from the Radegast station on August 9, 1944. About 70,000 people were sent there by the end of August. Most of them were sent directly to the gas chambers; some remained in Auschwitz or were sent to other Nazi camps.

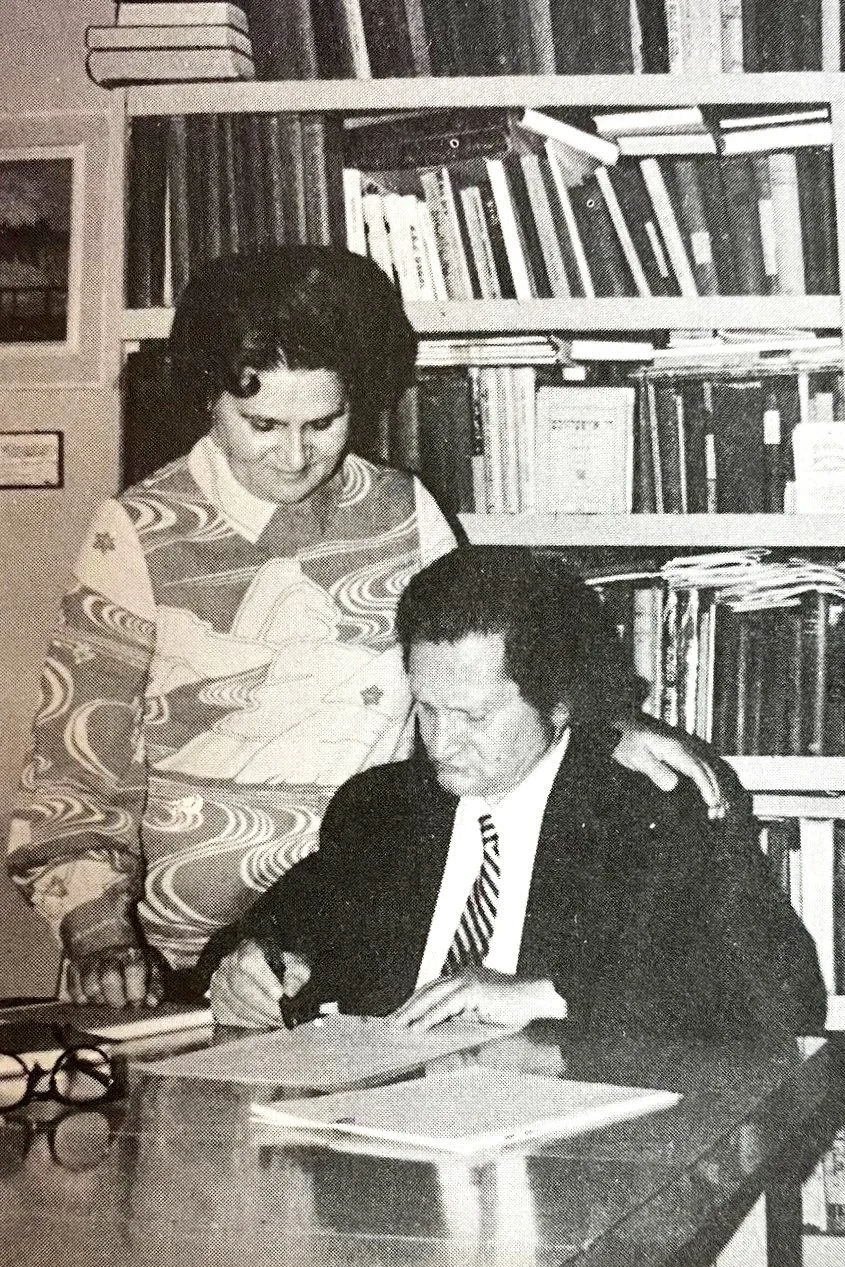

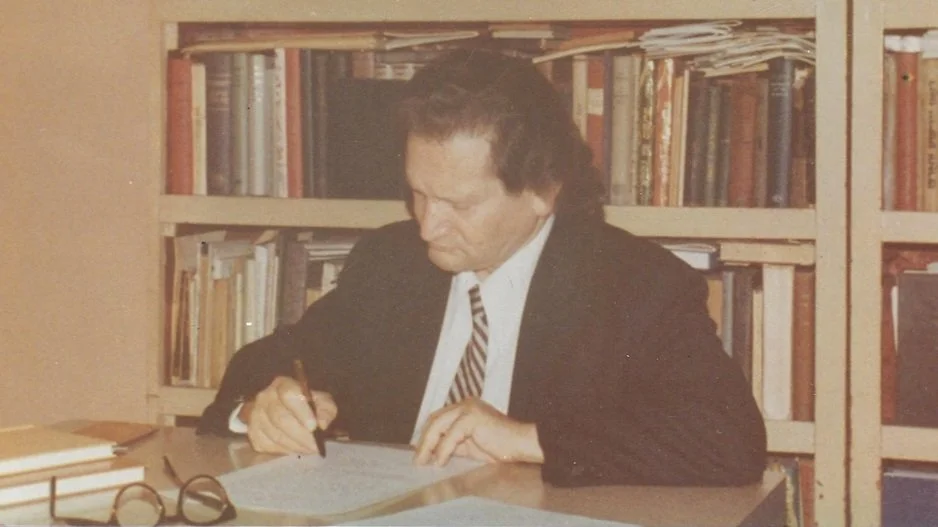

On August 24, 1944, Bryks was deported from the ghetto. He shared the train car with the writer Yeshaya Shpiegel and his family. On that day, after two reductions, the area of the ghetto had been diminished to four streets and eighty-three houses.

On August 29, 1944, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski and his family were deported to Auschwitz and left the ghetto in the last transport from the Radegast station .

On that day the Lodz ghetto ceased to exist. Over 68,500 Jews from the Lodz ghetto had been deported to Auschwitz.

Clean up

In September 1944, about 850 people were left in the ghetto to clean the area.

Another group was chosen by Hans Biebow himself to work in Germany. They were mainly the high ranking officials of the ghetto administration, engineers, lawyers, doctors and their families, about 600 people in total.

When the Soviet and Polish army units entered Lodz ghetto on January 19, 1945, out of the more than 245,000 Jews originally interred in the ghetto, they found only 877 Jews who had been left in the former ghetto by the Nazis to carry out clean-up operations.

This clean-up crew discovered Rachmil Bryks’s buried manuscripts and transferred them to the CZKH Historical Commission.