Works Overview

The term Holocaust literature actually encompasses two separate types of writing about this period: the literature written from memory after the war, and the literature written during the war, as a reaction to the events taking place in the ghetto and in the concentration camps.

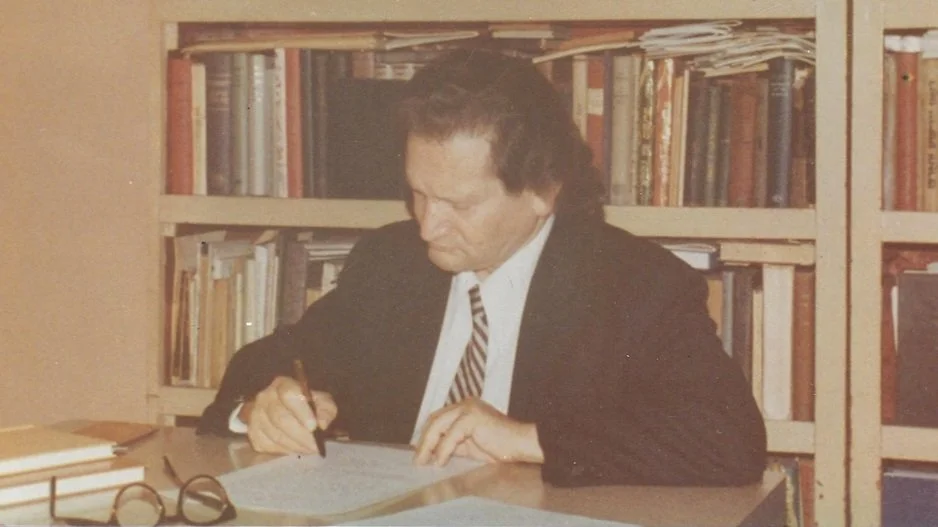

Bryks’s major published books about the Holocaust period were written from his memories after the war.

In order to truly understand the scope of his work and his writing talent, one must view his writings at the time of his experiences, the raw unembellished material he had written while he was a captive in the Lodz ghetto.

Bryks had told his daughter Bella, that throughout his four years in the Lodz Ghetto (May 1940 – August 1944), he had sat in the evenings after a hard day’s work and had written by hand many pages of poetry and prose, describing the hunger, pain, and anguish that the Jewish people were enduring.

He was a member of an underground group of Yiddish Writers which met at Miriam Ulinover’s home in the Lodz Ghetto each reading to her his poetry and awaiting her comments.

Realizing their historic importance, Bryks had buried his papers underground within the ghetto borders before he was deported to Auschwitz on August 24, 1944.

“All that I have discussed here was dictated to me by my intuition, while I was writing my books about the Churban, which I experienced myself... I wanted to write only documents — in my own way — that would shock and shake the reader.

— Rachmil Bryks, “My Credo”

How Bryks’ Poems were found

Bryks had believed his original writings were lost.

He was advised in Sweden in 1946, that his manuscripts had been unearthed when the ghetto was being cleaned, and that they had been brought to CZKH (Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna) which later became the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. For years, he tried unsuccessfully to receive photocopies of his unearthed poetry.

The management of the Institute demanded he come personally to Warsaw to see his manuscripts but Bryks refused to step again on Polish soil.

His frustration is revealed in an interview conducted in Yiddish in Petah Tikva in 1970 by Prof. Yehiel Szeintuch, in the framework of Oral Testimony for the Institute of Contemporary Jewry of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem:

"שיינטוך: צי גייט איר ווײַטער ָאן מיט אײַערע ָאנשטרענגונגען צו בַאקומען די כּתבי-יד ווָאס זײַנען אין ווַארשע?" "בריקס: ניין – ס'איז אוממעגלעך. איך הָאב נישט ליב, ווי מען זָאגט, צו שטויסן ווַאסער, צו קל אפּן אין ַא טיר ווָאס קיינער וויל נישט עֿפענען. איך הָאב געמַאכט איבער דעם ַא שטרוך. אֿפשר וועט דָאס ַארויסקומען און מע וועט זען ווָאס דָאס איז, ָאבער לויט דעם ווָאס גייט הײַנט אין פּוילן, איז נישטָא ווָאס צו 6 רעדן.

" Translation: “Szeintuch:

Are you still actively trying to receive your handwritten works that are in Warsaw?” “Bryks: No – it is impossible. I do not like, as we say, to tread water, to knock on a door that no one wants to open. I’ve crossed it out. Maybe it will happen and we’ll see what is there, but according to what is going on in Poland today, there is nothing to talk about.”

Bryks passed away in New York in October 1974 never seeing his documents again, never knowing which of his buried papers from the Lodz ghetto had been recovered. Bryks took this to heart and it caused him anguish.

His daughter, Bella felt a personal debt to her father and took upon herself the mission and the responsibility of bringing to light the mysterious pack of papers he had buried.

She began to research these writings in 2006 when she commenced her studies towards a Master’s degree in Yiddish Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

One of her classmates was a Polish student named Malgorzata (Gosia) Koziel Zaremba. She reached out to the Institute when she was in Warsaw and asked if she could photocopy some files from the Rachmil Bryks archive. Since she wasn’t related to Bryks, the management didn’t let her access all the files. However they allowed her to photocopy 10 items from the archives and send them to Bella.

Bella planned a week’s visit to Poland with her sister Myriam in August 2010. She coordinated with the Ringelblum Institute in Warsaw. Unsealing the archive of a writer whose archives have been sealed in the Jewish Historical Institute for six decades.

For several days, she sat in the Institute’s reading room and photographed every single piece of paper in the folders, a total of 240 photographs.

“Yiddish literature should be the tongue and the conscience of a hunted and tormented people.”

— Rachmil Bryks, “My Credo”

Catalog of the Rachmil Bryks Archive

According to the official list at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw (Żydowska Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuel Ringelblum), the Rachmil Bryks collection is comprised of 46 items.

An online catalog is available on the Jewish Historical Institute’s website. Out of 514 writers in the Institute’s archives, Rachmil Bryks is Number 39 (pages 18-19-20) and can be viewed at this link:

See http://www.jhi.pl/uploads/inventory/file/98/Utwory_literackie_226.pdf